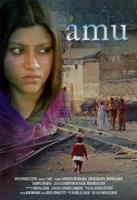

Amu - A Film that Stirs Emotions in a Modern Way

/RAJ MISHRA

/RAJ MISHRAWatching Amu at Toronto film festival was a first for me on three counts. I had never been to a screening at a film festival. I had never attended a screening that ended with the director and the executive producer fielding questions. It was also my first chance to see the award-winning and highly acclaimed film. Everything I had heard and read about Amu had not quite prepared me for the 100 minutes that I was to sit captivated.

Amu was released in India last January at the Mumbai international film festival, receiving its first award. It ran to packed theaters in several Indian cities for many weeks. It has received many more awards since then, has been applauded in the critic’s circles and much-admired by viewers. I had known about the outline of the story line in which a child orphaned during the horrific carnage of innocent Sikhs in Delhi in 1984 comes to uncover the facts as a young adult some 20 years afterwards.

I was also eagerly waiting for the first feature film made by director Shonali Bose whose earlier documentary, Lifting the Veil, on the impact of liberalization and privatization in India in the 1990’s had me yearning to see the cinematic rendering of a complex political-cultural milieu of our time.

The film was not a disappointment on any count. Much has been written about the film by many reviewers around the world during the past year. I have also written a commentary on the film after an animated discussion with young filmgoers in Delhi last winter. But nothing had prepared me to watch the film on a big screen at the downtown Toronto theater when the coloUrs and sounds of India’s capital city came alive in front of me. If one has to experience the complexities and the joys of life in urban India, this film captures it like no other film, almost as a documentary. The storyline and acting are a bonus, but what a bonus they make.

The film takes the viewer through an emotional journey that is heart-wrenching and exhilarating at the same time, evoking all the contradictory emotions of life in the 21st century. These emotions are brought to life in the superb acting of Konkana Sensharma, Ankur Khanna, Brinda Karat, Yashpal Sharma and others, handled masterfully by the director.

Ankur Khanna, acting as a college student in Delhi, renders ably the cultural currents the modern Delhite youth are subjected to – caught between the migrating rural peasants and laboUrers, the wandering NRIs, the political elite and their underlings as well as the middle strata in its eternal quest for upward mobility. In course of the film, this character discovers his identity as an Indian youth of the 21st century - conscientious, fearless and caring.

He takes a stand on the side of justice as he learns the truth about the Delhi riots through methodical investigation. The depiction of him falling in love with the lead female character Kaju, acted by Konkana Sensharma, is an interplay between individual and social love. The film captures very well how social love brings depth to the interpersonal relationship. Brinda Karat acts out a facet of modern life that many conscientious Indian women and men experience in their lives. She depicts the character of a volunteer trying to help the victims of the Delhi riots. Her life changes as she adopts an orphan whom she brings to the US to raise for a better future. She renames the child from Amu to Kaju and weaves a make-believe story about her identity to wipe off the debilitating memories of the riots.

Her dilemma as she rears Kaju in a Los Angles suburb builds the audience anticipation for its resolution. When Kaju pieces together the facts about her childhood and the tragic deaths of her parents, her mother does not relent to face the truth. Neither moralistic nor overwhelmed with guilt, she affirms her actions in an emotional but dignified manner. Her conflicting actions are placed in the context of her conscious pursuit to give a better life to an innocent child. The bond between the mother and the daughter is strengthened when both of them have the same social consciousness about the anti-Sikh riots.

Konkana Sensharma acts as the adopted child of the 1984 Delhi riots who has grown up believing to have been orphaned by an epidemic in India. As a college age NRI visiting India to seek her roots, Kaju starts out with a childlike innocence to learn about her parents and her childhood. She unravels the corrupt and sordid political life of India in the process: the criminal nature of the political system and its players – the bureaucrat, the police, the political class, the legal system, etc. Through her acting she brings forward the fearless and unrelenting spirit of the Indian youth, whether brought up in India or abroad. As she and her Indian friends uncover the depths of injustice in India’s social-political life, their spirits rise against the cruel system.

The film peels off layer by layer the injustices of modern India. It also shows the inherent unity of all the characters and their revulsion at the injustice around them even when they play out their parts in that cruel drama. The sweet stall owner, the auto rickshaw driver, the student, the mid-level bureaucrat and so on see themselves on the side of the young students and their pursuit for truth and justice.

The most refreshing aspects of the film turn out to be the modern and forward looking approach of all the characters within their complex environments, without succumbing to nihilism and degeneration nor compromising their conscience. Such a modern depiction of Indian values in art form uplifts and inspires the viewer to be unrelenting in the pursuit of justice. The director, who also is the author of the book with the same title, must be commended for creating such positive cinema.

At the Toronto Film Festival, one of the festival organizers introduced the film as one he personally had selected for its bold content. He commended the director for her fearless exposure of the complicity of the authorities in Delhi in the massacre of the Sikhs with impunity. During the question-answer session, the director explained how she had been directly involved in the relief work after the 1984 massacre when she was a college student and witnessed the tragedy first-hand. In response to the question from the audience as to who organized the violence and why, the executive producer explained that the real question that needs discussion is not who organized but who benefited. Looking from that angle, one will be able to answer a host of other questions including why the perpetrators still roam free and also why similar or worse massacres of the kind (such as in Gujarat) continue to occur. One may then be able to draw conclusions about the role these massacres play in Indian politics to keep the masses terrorized and disoriented as Indian State carries out economic, political and military reorganization to benefit the big business houses.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home